The final details of President Biden’s Infrastructure Plan will become clear in the coming weeks but it will surely include hundreds of billions of dollars for upgrades to energy and transportation infrastructure, including a proposed $15 billion for ‘demonstration projects for climate R&D priorities.’

One claim to this planned infrastructure investment is a clean energy mode of urban transportation that is emerging under the radar of the media, urban planners, and infrastructure investors. This mode is known as PRT.

Personal Rapid Transport, or PRT, is a form of transportation in which small self-driving podcars (autonomous vehicles) travel on their own dedicated guiderails, platforms, or in dedicated tunnels. Solar-powered PRT vehicles can travel directly to their network destination without stopping like a taxi, bypassing offline stations if there is no need to pick up or drop off passengers.

There are five small PRT-like systems in operation, including Heathrow Terminal 5 in the U.K. (Ultra PRT) and the recently completed Las Vegas Loop (The Boring Company). These systems have proven that PRT is an inexpensive and effective transportation option. However, they do not demonstrate how large, second-generation (G2) PRT networks can transform cities. Those systems have arrived.

A recent investment research report (freely available from Praetor Capital, www.praetor.capital) illustrates that the PRT industry has passed the tipping point and is set for rapid growth in the 2020s.

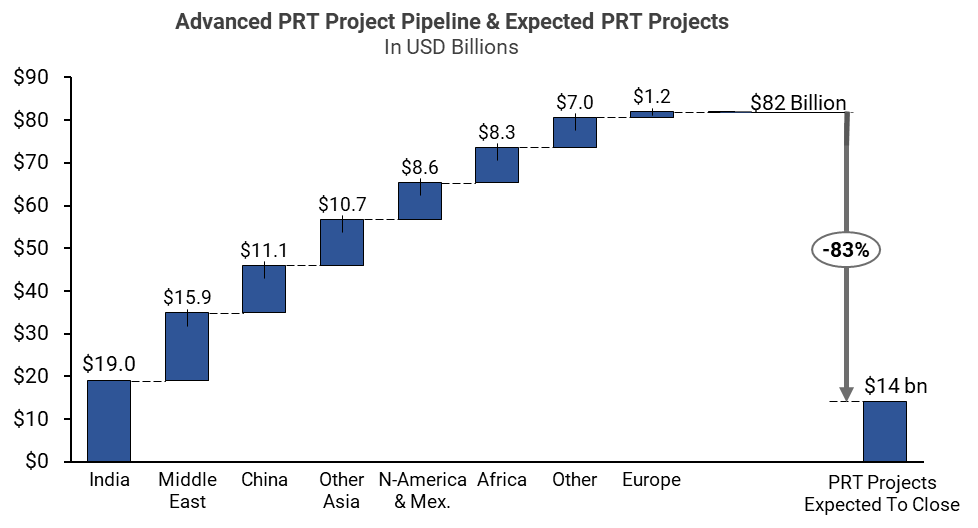

Discussions were held with 9 PRT firm CEOs for the research, which identified an $82 billion pipeline of advanced PRT projects worldwide*. Currently, most PRT activity is in India, China, and the Middle East. Of this $82 billion project pipeline, ~$14 billion of PRT projects are expected to break ground in the coming 3-5 years.

This $14 bn figure was determined project-by-project considering factors such as financial position, status, location, and the views of industry executives on execution odds.

The $14 billion project estimate is partly based on the 13 PRT networks that are already contracted or under construction in various cities and states. Examples are Chengdu Airport and the Jilin Province in China (Ultra / MTS and Ultra PRT), Brentwood CA (Glydways), Amsterdam Park & Ride and Mandai Depot, Singapore (2getthere), and Futran’s Philippines and Southern African systems. These 13 contracted networks constitute ~180 miles of PRT track, with 5 additional projects under bid in India at the time of writing (~129 miles).

The expected $14 billion of mostly developing-world infrastructure projects represents – in terms of scale – 5 to 7 city-wide PRT networks of elevated podcars on guiderails or platforms that move quickly from point to point, or city-wide tunnel networks with pods or Teslas. These existing projects already cover 100+ miles and 140+ stations.

The research demonstrates why PRT systems are gaining traction. The comprehensive overview of PRT opportunities provides a clear picture of a digital C21 transit mode that has several attractive attributes. These cannot easily be matched by traditional C20 transit like buses, personal cars, light rail, and subways.

The emergence of solar-powered PRT is timely given President Biden’s Infrastructure Plan and aggressive climate targets. PRT Industry executives propose that a $50 billion investment would transform 12 to 16 large US cities through the installation of 60+mile networks in each metro. That is the equivalent required spend for 3 US subway systems, and PRT podcars would be a better transit option for commuters on multiple levels.

PRT is the clean-energy solution to the urban transportation crisis that few are talking about. One would expect the 17 upcoming PRT projects to be the biggest story in transportation infrastructure, yet the emergence of terrestrial PRT has taken place almost completely under the media radar.

PRT CEOs cite several reasons for making the seemingly audacious claim that $50 billion would produce 12 to 16 large US PRT systems, and that these would produce operating profits for cities to boot:

First, large terrestrial PRT networks of 20+ miles are expected to be profitable at affordable fare levels (<$1 per 3-mile trip) and produce USD project IRRs of 15%+. Smaller networks would not have the scale to break even and may require subsidies. However, shorter networks will likely provide quicker, safer, more comfortable, and cheaper trips than alternatives such as BRT, Automated People Movers (APMs), and light rail.

The comparatively attractive PRT financials are partly a result of its low capital cost and operating costs.

Low terrestrial PRT capital costs (<$12 mill p/m). Several on-demand transportation technologies are maturing and – in some cases – are declining in price. Some examples of this are solar energy generation and storage, small electric motors, and light composite structural materials.

Low PRT operating costs. The vehicles are automated and therefore (obviously) require no driver. The pods only operate when they are needed (on-demand), using ridesharing for most trips to utilize the vehicle capacity more effectively. In addition, the small vehicles and electric motors require little maintenance.

The Boring Company has already proven that it can develop subterranean tunnels that form the basis for a larger PRT system at a fraction of the cost of a subway ($52 million for the 1.6-mile Las Vegas Loop first phase).

Profitable transit networks with attractive investor returns can be privately financed. This can be transformative for city budgets and creates a significant market opportunity for PRT. No longer will cities have to compete and wait for public transit funding; no longer will they have to subsidize transit operating losses.

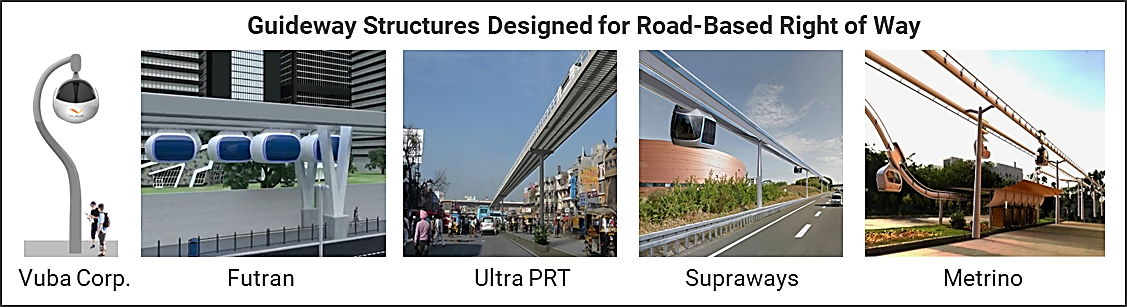

Second, elevated PRT systems can use the airspace above existing roads and sidewalks to provide flying-taxi-like urban transportation networks. Road-based right of way lowers capital costs by reducing or eliminating the need for land purchases, tunnels, and bridges. The current generation of PRT systems expects to transit passenger volumes equivalent to 6 road lanes, significantly reducing road congestion. The ~25-foot-high guiderail networks can free up urban surface space for other uses like parks or bike lanes. PRT also opens up the possibility of car-free urban zones.

Third, PRT Firms like Futran, Transit X, and Vuba will provide solar arrays above suspended vehicle networks. These become zero-emission urban power grids (~1 MW per mile) and can provide the climate benefit of eliminating ~8 million tonnes of CO2 from the atmosphere, the equivalent carbon sequestration of a 46 km2 forest. Installing a PRT network is hence an effective way for a city to meet its climate goals through a single bold action. One PRT CEO sites examples in Southern Africa where the power-generation and storage capability of PRT networks is a primary driver of state and investor interest.

Fourth, PRT autonomous control systems have already delivered the promise of self-driving vehicles as PRT is essentially a series of self-driving pods with their own dedicated ‘road’ (guiderail, platform, or tunnel).

The automation of in-service PRT systems has already achieved the Society of Automotive Engineers Level 5 Automation classification and completed 190 million injury-free passenger miles. The 2nd and 3rd generation of PRT autonomous vehicle software – currently under development and testing – will enable faster speeds (SkyTran is targeting 75-100 mph) and sub-2-second headways. The result will be a rapid and continuous flow of pods, smart routing to destinations, and nonstop trips. PRT networks can provide a shorter trip time than cars, including the wait time at stations.

Hence, PRT is already science fact, even though the guiderail networks and pods look like science fiction. In the words of an African financier, “This will convert Rwanda into Wakanda.”

All these PRT network attributes are attractive on their own. However, in combination,

they provide the basis for an extremely competitive transit mode. Further, several of PRT’s competitive advantages are sustainable. As closed systems, PRT networks will optimize their functioning over time and improve in every aspect of their performance.

PRT will complement self-driving cars and other C21 mobility innovations. The direct routing on a dedicated ‘road’ makes the difference, enabling PRT to maintain the standard of a faster, cheaper, safer, and more comfortable ride than road-based transit options. Danish urban designer Jan Gehl described the global road traffic congestion conundrum for cars – both self-driving and otherwise – best: “If you build more roads, you will have more traffic.”

Hence, PRT is potentially disruptive to the $1.5 trillion per annum global transit markets. The open question is this: What it will take to make PRT’s potential common knowledge among urban planners, politicians, and transportation reporters?

One purpose of this article is to address this challenge and shine a light on the opportunity that PRT represents for these stakeholders. One motivation that will surely turn heads is monetary gain.

PRT is transportation on-demand, which makes it comparable to Uber, Lyft, DoorDash, and Lime. It is also part of the same broader mobility industry as self-driving transport majors such as Apple, BYD, GM (Cruise), Alphabet (Waymo), Alstom, and Amazon (Zoox). Unlike these, though, the PRT provider industry – with the exception of The Boring Company – is largely unknown to infrastructure investors.

PRT firms like Ultra PRT, ModuTram, Futran, Transit X, and Vuba Corp. are undervalued and undercapitalized when compared with their on-demand peer companies. The estimated total combined value of these privately-held PRT firms – including The Boring Company – is $2.5 billion, with less than $500 million invested. This contrasts with the approximately $560 billion combined market capitalization for the 8 major public on-demand transportation peers (Uber, Lyft, BYD, GrubHub, DoorDash, LaLaMove, Meituan, and Alstom), and the approximately $200 billion of venture investment in the mobility ecosystem since 2010.

The research proposes that early investors in PRT companies have a potential $31 to $58 billion investment-gain opportunity. This is based on the tipping point assertion that once one large PRT project (20+ miles) demonstrates the mode’s attractive financials and autonomous flying-taxi-like attributes, capital will flow into PRT infrastructure projects and provider firms. Currently, there are 3 candidate city-wide contracted PRT projects in Africa and China.

The $31 to 58 billion valuation range of potential investment gain is based on the estimated $14 billion extrapolated financials of PRT projects. The resultant PRT industry growth rate and the provider firms’ current relative undervaluation (multiple-based) are integrated.

Funds and companies will likely enter PRT in the coming years on account of its disruptive potential. Put simply: there are billions to be made, starting with the existing pipeline of $82 billion of infrastructure CAPEX.

There are two potential entry points for those that wish to participate:

First, several of the PRT provider firms like Ultra PRT, Futran, Vuba, and ModuTram are raising equity capital in 2021. These firms are vertically integrated and provide products and services related to the development, management, and operation of urban PRT networks. They typically have their own vehicle, guideway, and control system designs and technologies.

Second, the PRT transportation network infrastructure projects that are typically structured as Public Private Partnerships (PPP) and use Special Purpose Vehicle (SPV) entities. In the cases of mid-sized and large PRT networks, the fare base is expected to produce returns (IRRs) of 15-40% and debt service coverage ratios that are higher than the top credit rating benchmarks for energy and transportation infrastructure projects. The author is aware of several large PRT projects currently sourcing capital in China, USA, India, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Both entry points into PRT provide investment gain opportunities and substantial potential new cash-flow streams for company segments beyond the on-demand transportation firms:

The public company currently best placed to dominate PRT is Tesla (TSLA), through its owner Elon Musk and his Boring Company, which considers itself a PRT company. The Boring Company’s marketing advantage can be applied to terrestrial PRT network products. There is little doubt flying (guiderail-based) ‘Tesla Pods’ could attract a good deal of attention and many potential customers.

When selecting between PRT provider firms and infrastructure projects, several capabilities are crucial:

Investing in PRT is not for those with a low risk tolerance. There is a risk the industry is not capitalized sufficiently in the coming years, resulting in the failure of several firms. The first large networks will pave the way for the industry, but there is no guarantee of commercial success for these vanguard G2 projects.

The specific risks inherent to PRT networks are political in that every PRT system needs a public city or state partner that is operationally collaborative in developing these systems at scale, and business-economic in delivering the required fare pricing, fare volumes, and expected cost. As a result, operational and financial risk instruments (e.g., credit guarantees or sovereign guarantees) will play an important role in this regard.

*SkyTran and The Boring Company declined to participate in the research. As a result, their sales pipeline is likely underestimated.

This post is a summary of a 52-page Praetor Capital PRT Investment Research Report. The full report can be freely obtained from www.praetor.capital or by emailing jan@praetor.capital.

DISCLAIMER: Jan Pretorius of Praetor Capital has investments in PRT companies listed in this report: Vuba Corp and a Futran technology. Mr. Pretorius is also the Vuba Corp CFO.

This Research Report reflects Praetor Capital’s views on PRT but is subject to change without notice and does not claim the information is accurate or complete. Praetor Capital is not being compensated directly for any view related to this Research but may have, or may establish, advisory relationships with the firms discussed.

This Research does not constitute the provision of investment, legal, or tax advice. The early-stage companies and infrastructure projects discussed in this Research are high-risk and not suitable for most investors, who must make their own investment decisions.

In no event shall Praetor Capital be liable for any damages including, without limitation, direct or indirect, special, incidental, or consequential losses or expenses arising in connection with the data and opinions presented in this Research.