Many Americans see the future crowding into the present and some of the innovations ahead unnerve them, especially as they reshape ideas about human dominion.

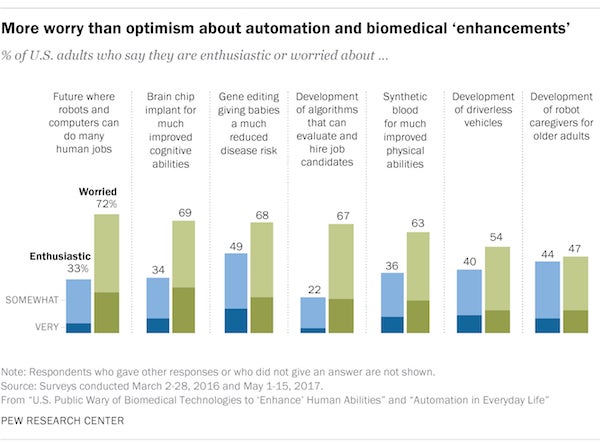

Studies by the Pew Research Center, titled “U.S. Public Wary of Biomedical Technologies to ‘Enhance’ Human Abilities” and “Automation in Everyday Life,” find striking wariness among Americans as they think about advances in robotics, artificial intelligence (AI) and biomedical innovations that could significantly alter human capabilities. Queried about different scientific and technological developments, more Americans say they are worried than say they are enthusiastic about six out of seven of these developments. This less-than-eager public outlook can play an important role in shaping adoption of the technologies and the policy debates that will govern their role in society.

One source of collective apprehension stems from worry over potential risks and unintended consequences from emergent technologies. For example, when asked about using brain implants for improved cognitive abilities, focus group respondents often raised concerns about hacking and the possibility of outside forces gaining control of people’s minds. And—in a survey conducted nearly a year before some road tests of autonomous vehicles were halted after a fatal traffic accident—many people raised concerns about the safety of driverless vehicles should computer glitches occur.

There’s a common supposition that the very newness of emergent technologies is the key driver of collective anxiety. Thus, advocates argue that public resistance to scientific and technological developments will fade as people become more familiar with them. Pew Research Center surveys find that people who report having heard more about emergent technologies—such as autonomous vehicles—tend to be more enthusiastic than those unaware of these developments. However, it is not clear whether a connection between familiarity and enthusiasm will persist over time. History includes examples such as that of in vitro fertilization where greater familiarity has coincided with greater acceptance, but also developments such as cloning where public resistance has persisted over time.

The foremost insight from Pew Research Center studies is that public wariness about emergent technologies is connected with concern over the potential loss of human agency and free will. For example, the idea of machines taking over the act of driving lead one survey respondent to lament, “I want to be in control and not have the machine choose what’s best for me.” Some believe that human performance surely outstrips that of algorithms. “A computer cannot measure the emotional intelligence or intangible assets that many humans have,” argued one young woman who opposed the use of hiring algorithms as part of the job-application process. The notion of implanting a brain chip to enhance cognitive abilities lead one focus group participant to observe, “You kind of …lose individuality because you have all these kind of super-people that can remember everything, [but there are] no individuals anymore. They’re all just the same robotic people.”

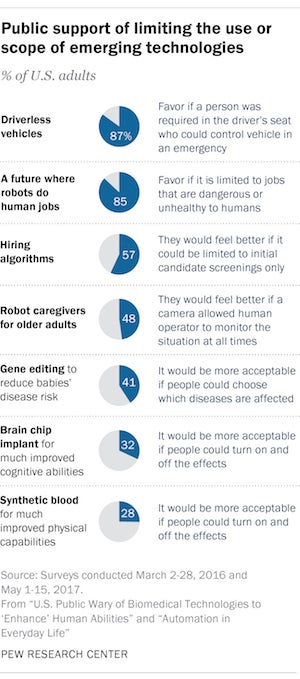

Across all seven of the developments in the Pew Research Center studies, proposals that would increase control over these technologies and keep humans in charge were met with greater acceptance. For instance, the vast majority of Americans (87 percent) would favor the idea of requiring autonomous vehicles to have a human driver available at all times who could take over the vehicle if needed. Some 85 percent of Americans would favor limiting workforce automation to jobs that are “dirty or dangerous” for humans. Some 57 percent said they would feel better about the use of hiring algorithms if the algorithms were only used during initial job-candidate screenings and then face-to-face interviews were conducted among those who got through the initial screening.

Across all seven of the developments in the Pew Research Center studies, proposals that would increase control over these technologies and keep humans in charge were met with greater acceptance. For instance, the vast majority of Americans (87 percent) would favor the idea of requiring autonomous vehicles to have a human driver available at all times who could take over the vehicle if needed. Some 85 percent of Americans would favor limiting workforce automation to jobs that are “dirty or dangerous” for humans. Some 57 percent said they would feel better about the use of hiring algorithms if the algorithms were only used during initial job-candidate screenings and then face-to-face interviews were conducted among those who got through the initial screening.

Similarly, the public is more accepting of biomedical technologies that would change human abilities if humans had control of the nature and permanence of the changes. Some 41 percent of Americans say gene editing for babies to prevent serious diseases later in life would be more acceptable to them if people could choose which diseases would be affected, while just 17 percent said this would make gene editing for babies less acceptable. And 32 percent say they would find the idea of brain chip implants more acceptable if the brain-enhancing effects could be turned on and off, while just 16 percent say this ability would make it less acceptable to them and about half (49 percent) say it wouldn’t change their views about this either way.

+1-786-628-7980

+1-786-628-7980

Sign Up/Sign In

Sign Up/Sign In